The Pirate Queen’s Slave Traders

Elizabeth I and the Conjuring of the British Empire

Part One

Copyright ©2024 by Independent History and Research • Revisionist History Website

Reading time is approximately 45 minutes

The vast majority of the historians of the Elizabethan period, however sophisticated they may be in the study of other aspects of the life of Queen Elizabeth I, put forth a comic book vision of her and those who served her in terms of English Protestants equal liberation of mind and body; Spanish Catholics equal inquisitorial sadism and enslavement.

English Protestant monarchs in this fantasy are but one step removed from flower children, tip-toeing over fields of religious controversy to embrace diversity of opinion with respect to freedom of conscience, while the Spanish are heresy-hunting, dark-skinned, hook-nosed personifications of horror.

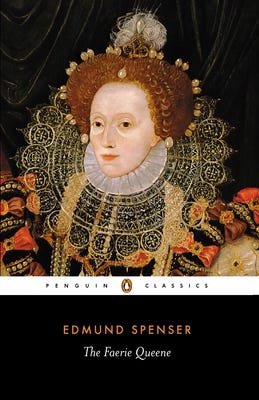

Lifting the Veil on Spenser’s Fairie Queen and the Identity of the “New Isis”

For good reason the western secret societies in Britain have long idolized Queen Elizabeth I. This trend was prevalent in her lifetime when Edmund Spenser in his self-validating, canonical Fairie Queen epic intimated that she was the “New Isis”:

“It is in the Faerie Queene (Book V) that we meet Isis as a symbol of Justice and equitable queenly rule. Spenser wanted to associate Elizabeth's rule with an ancient Golden Age ruled over by another strong queen: Isis, the Divine Queen of Egypt. Spenser tells us that Isis was ‘a Goddess of great power and soverainty’ and that justice and equity were among her blessings. So too are power, sovereignty, justice, and equity hallmarks of Elizabeth’s reign.” (Cf. “Isis & the Faerie Queene”).

In Book V of the Fairie Queen the poet emphasizes a positive view of Egypt by invoking the many magnanimous pagan myths surrounding the goddess Isis. In her study of Ancient Egypt and the Fairy Queen, Genavieve Alt writes:

“The Faerie Queene allegory extends to the British crown as well as Spenser’s own life. Queen Elizabeth I, who came to the throne after the death of her half-sister Mary Tudor, was generally seen as a benevolent, powerful and unmarried female ruler—the first of her kind. Elizabeth never married, never produced an heir, and took it upon herself to act as both masculine and feminine ruler.

“In a famous speech made to British troops at Tilbury on August 9, 1588, Elizabeth acknowledged her dichotomous gender roles, saying ‘I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and a king of England too.’

The representation of Elizabeth as embodying both masculine and feminine traits is allegorized in Books III and V of the Faerie Queene through (the character of) Britomart. At the very beginning of Britomart’s story in III. ii, Spenser introduces the looking glass given to her father by the wizard Merlin.

“According to Dorothy Stephens, “Queen Elizabeth regularly consulted an astrologer, John Dee, who used a crystal ball.’

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Michael Hoffman's Revelation of the Method to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.