A Pilgrimage to Decency and Form

An uplifting cinematic tale of the traditional people our civilization continues to produce in the midst of the post-modernist meltdown

I was listening to Sirius XM’s “Symphony Hall” the other day. They were playing Aaron Copland’s “Rodeo.” After David Thomas Roberts, Copland is my favorite American composer. For this writer, “Rodeo” evokes the poignancy of summer in our forests, mountains and small towns more than any piece of classical music.

Listening to it gave me pause in my work week to fault myself for what little time I have expended this summer on what Thomas Gray hallowed in his famous Elegy:

Far from the madding crowd's ignoble strife,

Their sober wishes never learn'd to stray;

Along the cool sequester'd vale of life

They kept the noiseless tenor of their way.

Though your editor resides in the foothills of mountain Idaho, I am routinely in the midst of research and ideological strife as these “Revelation of the Method” columns demonstrate. I have been hoping for a respite of late but massacres have followed betrayals, Epstein client lists, more atrocities, treachery in high places, and more Epstein.

A chance to take stock, gaze at the summer night sky, reappraise how well I have used the gifts and the time my Creator has allotted me have not been availing. I do tend my garden daily and the fruit trees I planted a few years ago to save the expense of purchasing organic peaches and apples at the market.

Pat Buchanan Deserves Better

While hunting in my archives this week for a document, I came upon a photo of Patrick J. Buchanan and a news article related to when he campaigned for president in Spokane, Washington more than 20 years ago. I attended his speech at a local hotel in the company of his Idaho delegate to the Republican National Convention. My wife arrived late to the event with some of our kids, “herding four children” as the local newspaper memorably described the precocious parade.

I have had many bones to pick with Mr. Buchanan over the years and I won’t rehash them here. There is no denying, however, that he was “America First” when Trump was a playboy cavorting with Epstein.

Pat was among the first American statesmen in post-modern times to seriously seek to regain control over our southern border and undertake a non-interventionist (not “isolationist”) foreign policy, while restoring our nation’s moral fiber and striving for greatness.

His strong sense of the criminality of the Israeli oppressors of the Palestinians led him to refuse the genuflections to Zionist royal prerogative which almost all national figures were (and are) required to make.

His “Culture War” oration to the nation at the Republican National Convention in August of 1992 (start at 4:40) showed the world that he was indeed “a great communicator,” though the politicians on whose behalf he spoke that night were unworthy of him.

His principled loathing for the Bush GOP’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan was unwavering.

Though Pat possessed none of the arrogance of the “Ozymandias” who is at the center of Shelley’s poem of that name, the impermanence of fame and renown certainly applies to him in his dotage (he’s 86), which he is living largely in obscurity. Trump has bestowed no Medal of Freedom on him as he did for his financier, Miriam Adelson, and golfer Tiger Woods.

Pat’s visionary books are seldom referenced by the contemporary national Conservative movement. In the amnesia and disrespect to which Buchanan has been subjected one is afforded a glimpse of the transience of prestige and celebrity, and the fickle nature of the “Buchanan brigades,” the populist wing of the Conservative movement of which Pat was the architect. One is haunted by his fate. It is a reminder that whatever we are doing it had better be for God and not man (I Peter 1:24).

This week I’m pledged to compel myself to do what I can’t do in winter — read outdoors under a leafy deciduous tree, in our pristine clean air, with the Selkirk mountains before me, reaching for the sky. When I do I’ll salvage what Copeland’s “Rodeo” summons.

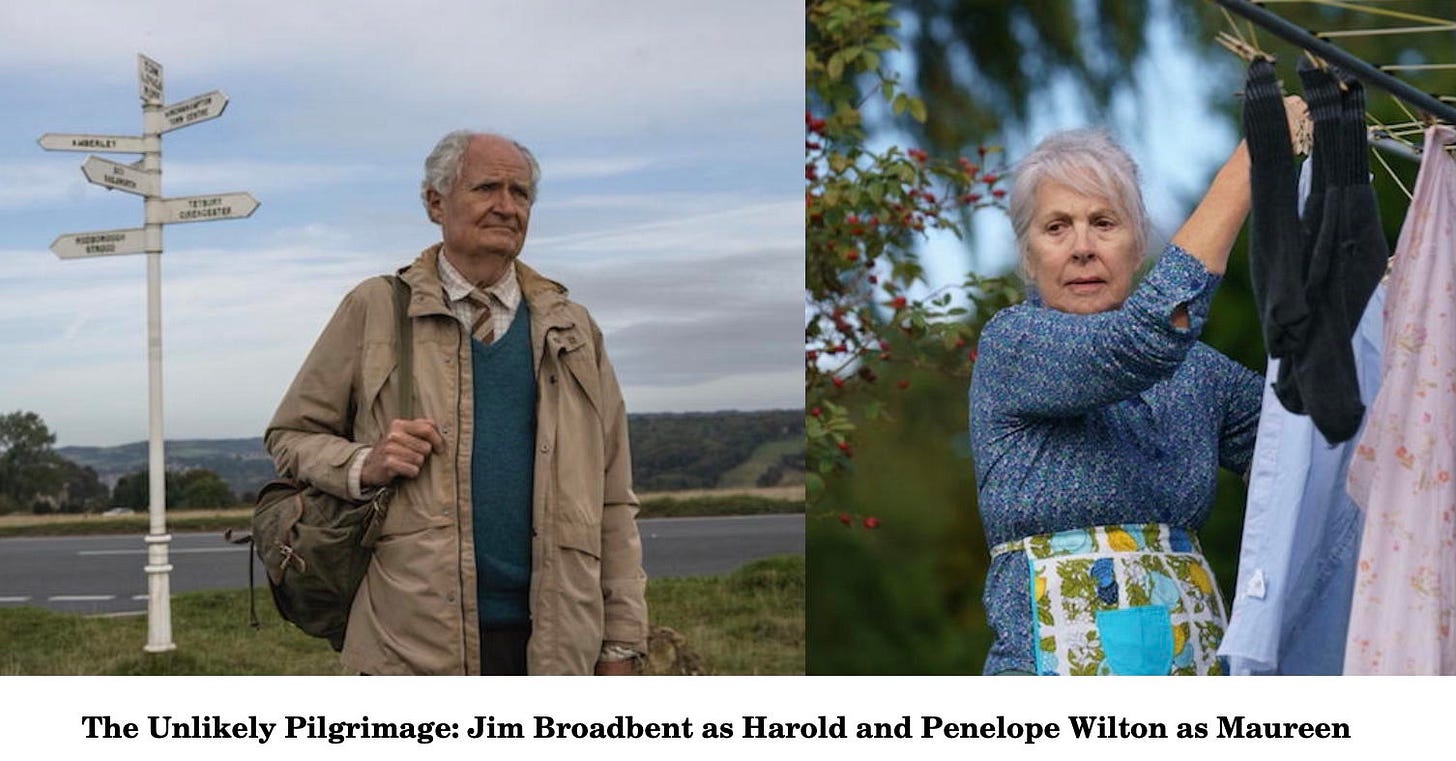

A Pilgrimage By a Promise Keeper

Recently I had an epiphany indoors in front of a television, where I watched a 2024 British film, The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, starring Jim Broadbent and Penelope Wilton and written by Rachel Joyce. It rather took my breath away because it is an artifact from another era, yet produced in our time. It somehow eluded the woke censorship filter, being a cinematic paean to a patriarch and the recovery of lost dignity, decency and form, in a time when all of three are under assault in favor of the enhancement of misery and a come-as-you-are casualness, which has dissolved into a march of the disheveled, where every ounce of self-respect is drained, either from a belief in a misconceived egalitarianism, or a complete collapse of standards and form.

Contemporary English people born in the 1940s and ‘50s continue in large part to maintain that form. When I trekked with my eldest daughter to England to visit archives and colleagues, with a side excursion to the Brontë family home in the town of Haworth, where we stopped in a middle class eatery packed with retired English women, all of whom were dressed with dignity.

To the mortification of my children I am sometimes given to spontaneously addressing strangers who strike my fancy, whether individually or in crowds. “Excuse me ladies,” I said in Haworth. “I’m from America and I want to express to you how much I admire how well you are dressed.” They smiled and there was self-conscious laughter, after which a sturdy matron stood up and thanked me, saying, “And we’re pensioners!” — meaning they were all on a fixed income.

In The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, Harold and Maureen Fry are a couple living in a marriage in Devon that on the surface is not much more than civil. They are middle class pensioners. Their suburban home is dark. Some tragedy lurks in their past. Their only child is absent. The prospect of grandchildren is a dream.

Yet the manner in which they talk, dress and carry themselves conveys a je ne sais quoi hint of character, decency and inner reserves.

The movie achieves the appearance of post-modernist similitude: neither Harold nor Maureen has religious faith. Their only child is so rarely seen it is as if they have no family. The marriage is on ice, due to a conflict relating to the absence of their son. Their fading prospects will be familiar to a western audience of diminished people who find themselves in a desert of sterility.

For American viewers the surprise registered at seeing Harold for the most part always in a sport coat and tie, even around the house, and his wife in a dress, is not discomfiting or off-putting because in the fundamentals of the existential exhaustion in which post-modern people dwell, the couple in the movie do not disappoint. The audience can relate to them on that basis. There is little likelihood of a rupture in their engagement with the film’s characters. As we shall see, this is a set-up.

When he receives a letter from Queenie Hennessy, a former lady friend now dying of cancer in a hospice 500 miles distant, the usually sedentary Harold impulsively vows to walk the entire way without proper shoes or provisions.

He telephones the hospice to announce to the staff that he “will keep walking and she must keep living.” They at first discourage him. Maureen meanwhile, is appalled. Her emotions turn to bitterness at how she has been seemingly abandoned by her husband’s apparent irresponsibility, bordering on perhaps madness.

Off he treks, indifferent to rain and shoddy accommodations, sleeping in his tie and coat in hovels, cheap motels and barns. The movie’s concealed benevolence begins to emerge as he is helped along the way by various kind folk. His feet become infected and blistered and he is cared for by a Slovakian immigrant janitor who was a medical doctor in her native country and who can’t obtain a physician’s license in Britain. Her uncomplaining, matter-of-fact approach to life while expertly treating Harold presages further Good Samaritan encounters, without making the movie treacly or sentimental. There are some hard edges here as well.

As he takes his lunch at a rest stop along the highway he meets a journalist unawares. The reporter questions him about his journey and his promise to Queenie. The next day the story is printed and gains national attention. Soon he’s revered and endowed with a cult-like status, attracting a band of followers determined to accompany him the hundreds of miles, all the way to the hospice. They print “pilgrimage” t-shirts. He removes his coat and tie and dons one of the shirts, offering no objection to the circus-like atmosphere.

At this juncture I surmised the movie was descending into a hippie vibe where the “uptight” former businessman would “shed his inhibitions” and go full flower child, severing his ties to his wife in the usual middle-age-crazy “liberation” that destroys all the “for better or worse” vows we make at our wedding.

No doubt, I reflected, Queenie was his mistress at one time and Harold is completing the last devoted act of his adultery (or as they say, “affair”). From the crowd accompanying him he may even be able to select a substitute gal pal. His “repressed” marriage to Maureen will of course be abandoned in favor of “following his own star, reclaiming agency over a life marked by passivity,” and “being true to himself” — opting for a “courageous release from a fractured marriage.”

Ah, but I was wrong; so wrong. All those 39¢ New Age psychology shibboleths have no place in this film.

After he has been on the road several days, he and Maureen speak by telephone. Her bitterness has cooled and turned to resignation. Her journey, though interior, mirrors Harold’s exterior one, as she navigates her solitude and considers the possibility of a reconciliation. She has slowly come to respect her husband’s commitment to keeping his promise to Queenie.

Harold asks her to join him on his walk. A neighbor drives her to meet him. They have tender but not maudlin moments together. Maureen will not join him, though she wholeheartedly encourages him to complete his “pilgrimage.” It’s not to Walsingham, as it would have been five centuries ago, but it is an act of faith nevertheless—for Queenie’s welfare.

Eventually Harold’s followers drift away and he is alone again. He dons his tie and sport coat, the worse for wear. This unassuming, disarming man whose understated grace is his most attractive aspect, questions himself and the purity of his intentions. Harold is in some respects wistful and unsettled. This is a movie true to life, without contrived resolutions.

The physically drained Harold’s arrival at the Catholic hospice, staffed by nuns, is not what we expect. Queenie’s condition contrasts with Harold’s combination of resilience and vulnerability.

There are surprises I have omitted so as not to spoil the experience for potential viewers. There are family secrets. There is also a mystical note to the ending that balances what appears to be a dispiriting denouement.

Spoiler alert: skip the next two italicized paragraphs if you wish to maintain a tabula rasa about the movie.

Maureen and Harold appear to be reconciled until we realize that Harold had never for a moment required reconciliation, in that he had not been alienated from his spouse: his trek entailed no thought of leaving Maureen. He was and is true to her. The walk to Queenie was a pilgrimage, not a desertion. His marital attachment to his wife— his ordinary, everyday love for her—was never for him in question. In a time when marriage vows are made to be broken Harold‘s promise to Queenie was of a piece with the loyalty he had vowed to his wife decades before.

His duty to Queenie is a reflection of his commitment to Maureen, not an abandonment of it. Harold Fry is a promise keeper in every way that matters. The movie extols that fact with finesse and subtlety, rather crusading didactically to make a heavy-handed point, and therein rests its charm and effectiveness.

Pilgrims travel often in risky ways (the root of the word travel is travail). When they are successful they are altered by their encounter with the divine, and on their return home the intensity of their spiritual commitment is often enhanced.

The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry is a profoundly conservative family values film, representative of the people our civilization has traditionally nurtured; that it was produced in our time is a cause for hope.

Some may say that my interpretation is too ponderous a philosophical burden to impose on a low key character-study. Yet, it is in the simplicity of the telling that the slowly revealed message is compellingly conveyed. If it had been telegraphed, a 21st century audience would reject it.

What happens in this film is a series of reversals of the viewers’ expectations, culminating in an affirmation of decency without trumpets and fanfare, as part of lives that appear ordinary, and are overlooked in a celebrity-driven media world pumped up on the steroids of voyeurism and misplaced veneration of that which is unworthy of our devotion.

[The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry may be viewed on cable television by Amazon Prime subscribers, or rented on one’s computer or “smart” TV from YouTube, or purchased on DVD].

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF KNOWLEDGE CONTRA CANCEL CULTURE

Copyright ©2025 by Independent History and Research • Box 849 • Coeur d’Alene, Idaho 83816 USA | www.RevisionistHistory.org

Recent Studies by Michael Hoffman

Pam & Patel and the Revelation of the Method

Freemasonry and the Founding Fathers

I am grateful to the paid subscribers who make these columns possible. Thank you.

I will continue this Truth Mission for as long as I have the resources to do so. Securing those resources is a constant struggle. We have not yet obtained enough paid subscriptions to sustain the work required to produce this column weekly.

Donations toward the support of my research, writing and broadcasting are gratefully received: P.O. Box 849, Coeur d’Alene, Idaho 83816—or at this link. Thank you.

Revisionist historian Michael Hoffman explores the ascendance of the Neoplatonic-Hermetic-Kabbalistic mind virus in his book The Occult Renaissance Church of Rome. He explicates the alchemical processing of humanity in Twilight Language. He is the author of eight other volumes of history and literature including Secret Societies and Psychological Warfare, as well as Usury in Christendom, Judaism Discovered, and Adolf Hitler: Enemy of the German People.

Michael has written extensive introductions to Alexander McCaul’sThe Talmud Tested, Johann Andreas Eisenmenger’s Traditions of the Jews, and The 1582 Rheims New Testament. Purchase our 2025 Revisionist History® Calendar here.

Mr. Hoffman is a former reporter for the New York bureau of the Associated Press and a former paid consultant to the news department of the New York Times. Michael’s books have been published in translation in Japanese and French. Listen to his broadcasts on the Revisionist History® podcast, and find him on X (Twitter).

Revisionist History® is registered with the United States Patent and Trademark Office as the trademark of Independent History and Research, Box 849, Coeur d’Alene, Idaho 83816. All Rights Reserved.

Roscoe himself commenting this week:

It was gratifying to read Michael's comments on Pat Buchanan, who twice within the Republican party in 1992 and 1996, sought the nomination in the Presidential race and in 2000 ran as an independent. He was correct on three big issues: he opposed the off shoring our manufacturing, endless military intervention in other parts of the world (what Harry Elmer Barnes called "perpetual war for perpetual peace") and unrestricted immigration.

Of course, the Republican party would not stand for this. In December 1991, National Review (a silly rag that long ago appointed itself as the keeper of the Overton Window as to just exactly what opinions "conservatives" are allowed to express) basically devoted the entire issue to giving William F. Buckley Jr. free rein in the hatchet job of asking "is Pat Buchanan an anti-semite?" This later spun off a book, "In Search of Anti-Semitism," which Nathan Glazer reviewed in the New York Times and from which the following excerpt is taken.

"Two passages suggest he is edging toward this conclusion. Mr. Buckley argues that anti-Semitism morally disqualifies a person from seeking public office, and then asks, Would anti-Catholicism disqualify a candidate? A Catholic himself, Mr. Buckley says no: "There is no geographical promontory out there, populated by Catholics who are exposed to terminal persecution. . . . I am ready to concede that in our world, in our time, Jews have inherited distinctive immunities." And again, going even further, he says: "Anyone who gives voice, especially if this is done repeatedly, to opinions distinctively, even uniquely, offensive to the security of settled Jewish sentiment involving religious or ethnic or tribal pride engages in anti-Semitic activity."

In his scathing obituary of Buckley, "William F. Buckley Jr., RIP--Sort Of," Peter Brimelow suggested that,

"I do know that Buckley's political ambitions were not merely symbolic. After his race against Lindsay, he convened a private meeting including F. Clifton White and long-time National Review Publisher Bill Rusher, both veterans of the Draft Goldwater movement, to discuss the question of how he could run for president. They assured him, very unimaginatively I believe, that it was unthinkable. So Buckley stepped aside. But had he and not James won the Senate race in 1970, he would have been a contender. It was a fatal mistake. Conceivably, it could have broken his heart.

"Unquestionably, in my view, it explains the fratricidal savagery of Buckley's 1992 attack on Pat Buchanan, a fellow Irish Catholic conservative who had dared to make the jump from pundit to presidential candidate. As a much-celebrated Catholic, Buckley must have known that Envy is one of the Seven Deadly Sins. But that does not mean he was immune."

Buchanan, a gracious, intelligent man with a sense of humor and with decent instincts, never stood a chance in a party that likes mean spirited people: the Bushes, Dole, McCain, Romney, Trump. But I am grateful that he made the effort.

Katya chiming in behind my husband, Roscoe, who not only brought Pat Buchanan into my life, but also, just yesterday, educated me regarding Ozzie Osborne, of whom I can say with joy I had never heard.

But simply, following the Copeland theme with “Fanfare for the Common Man”, composed at a time when America was so filled with hope, I want to suggest to readers the books of a fairly obscure Catholic writer, Stephen Faulkner. His theme is also Pilgrimage: just a few years ago, with almost no money, he took his teenaged son to retrace the route of Father Jacques Marquette by canoe from St. Ignace, at the northernmost tip of Lake Michigan, all the way to St. Louis, MO, all by hand-paddling, no motors, an absolutely extraordinary contemporary pilgrimage through a forgotten current of American history, providing such balm to our minds so overworked today by the incessant assembly line of dire news. He and his son manage to find a Catholic Church nearly every Sunday, climbing from the banks of their shoreline camps, to attend Mass. A pilgrimage of two months, of spirit, of history, of reflection, of what we might be capable of without our machines, of time out of mind —all with very little money. The book is called “Waterwalk” and is filled with stories of Pere Marquette, with poetry, Augustine, Scripture, and the cruel pressures of modern life.

Faulkner’s second book, called “Bitterroot,” describes father and son’s overland trip to trace the route of Father De Smet through the West. They do as much on foot as they can manage in our highway covered land, which is another of the loud but invisible tyrannies of our lives.

These books by an obscure Catholic writer are contemporary chronicles of “decency and hope,” of faith and commitment, as Michael describes. I believe a movie was made of “Waterwalk,” but the books are a very restful and inspiring read. So that we might remember who we are and where we came from, and how much we actually owe to our forgotten holy Fathers Marquette and De Smet. My plan is to send Steven Faulkner a copy of Hoffman’s “The Occult Renaissance Church of Rome,” or maybe “Usury in Christendom” for Christmas this year. Such reading will be a pilgrimage, maybe even like running and capsizing in a rapids. (They’ll be maytagged, says Roscoe! I’ll leave the politics to him.)

Thank you, Michael, for the lovely interlude.